Mobile App User Privacy Protection

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: The MASTG is not a legal handbook. Therefore, we will not deep dive into the GDPR or other possibly relevant legislation here. This chapter is meant to introduce you to the topics and provide you with essential references that you can use to continue researching by yourself. We’ll also do our best effort to provide you with tests or guidelines for testing the privacy-related requirements listed in the OWASP MASVS.

Overview

The Main Problem

Mobile apps handle all kinds of sensitive user data, from identification and banking information to health data. There is an understandable concern about how this data is handled and where it ends up. We can also talk about “benefits users get from using the apps” vs “the real price that they are paying for it” (usually and unfortunately without even being aware of it).

The Solution (pre-2020)

To ensure that users are properly protected, legislation such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe has been developed and deployed (applicable since May 25, 2018), forcing developers to be more transparent regarding the handling of sensitive user data. This has been mainly implemented using privacy policies.

The Challenge

There are two main dimensions to consider here:

- Developer Compliance: Developers need to comply with legal privacy principles since they are enforced by law. Developers need to better comprehend the legal principles in order to know what exactly they need to implement to remain compliant. Ideally, at least, the following must be fulfilled:

- Privacy-by-Design approach (Art. 25 GDPR, “Data protection by design and by default”).

- Principle of Least Privilege (“Every program and every user of the system should operate using the least set of privileges necessary to complete the job.”)

- User Education: Users need to be educated about their sensitive data and informed about how to use the application properly (to ensure secure handling and processing of their information).

Note: More often than not apps will claim to handle certain data, but in reality that’s not the case. The IEEE article “Engineering Privacy in Smartphone Apps: A Technical Guideline Catalog for App Developers” by Majid Hatamian gives a very nice introduction to this topic.

Protection Goals for Data Protection

When an app needs personal information from a user for its business process, the user needs to be informed on what happens with the data and why the app needs it. If there is a third party doing the actual processing of the data, the app should inform the user about that too.

Surely you’re already familiar with the classic triad of security protection goals: confidentiality, integrity, and availability. However, you might not be aware of the three protection goals that have been proposed to focus on data protection:

- Unlinkability:

- Users’ privacy-relevant data must be unlinkable to any other set of privacy-relevant data outside of the domain.

- Includes: data minimization, anonymization, pseudonymization, etc.

- Transparency:

- Users should be able to request all information that the application has on them, and receive instructions on how to request this information.

- Includes: privacy policies, user education, proper logging and auditing mechanisms, etc.

- Intervenability:

- Users should be able to correct their personal information, request its deletion, withdraw any given consent at any time, and receive instructions on how to do so.

- Includes: privacy settings directly in the app, single points of contact for individuals’ intervention requests (e.g. in-app chat, telephone number, e-mail), etc.

See Section 5.1.1 “Introduction to data protection goals” in ENISA’s “Privacy and data protection in mobile applications” for more detailed descriptions.

Addressing both security and privacy protection goals at the same time is a very challenging task (if not impossible in many cases). There is an interesting visualization in IEEE’s publication Protection Goals for Privacy Engineering called “The Three Axes” representing the impossibility to ensure 100% of each of the six goals simultaneously.

Most parts of the processes derived from the protection goals are traditionally covered in a privacy policy. However, this approach is not always optimal:

- developers are not legal experts but still need to be compliant.

- users would be required to read usually long and wordy policies.

The New Approach (Google’s and Apple’s take on this)

In order to address these challenges and help users easily understand how their data is being collected, handled, and shared, Google and Apple introduced new privacy labeling systems (very much along the lines of NIST’s proposal for Consumer Software Cybersecurity Labeling:

- the App Store Nutrition Labels (since 2020).

- the Google Play Data Safety Section (since 2021).

As a new requirement on both platforms, it’s vital that these labels are accurate in order to provide user assurance and mitigate abuse.

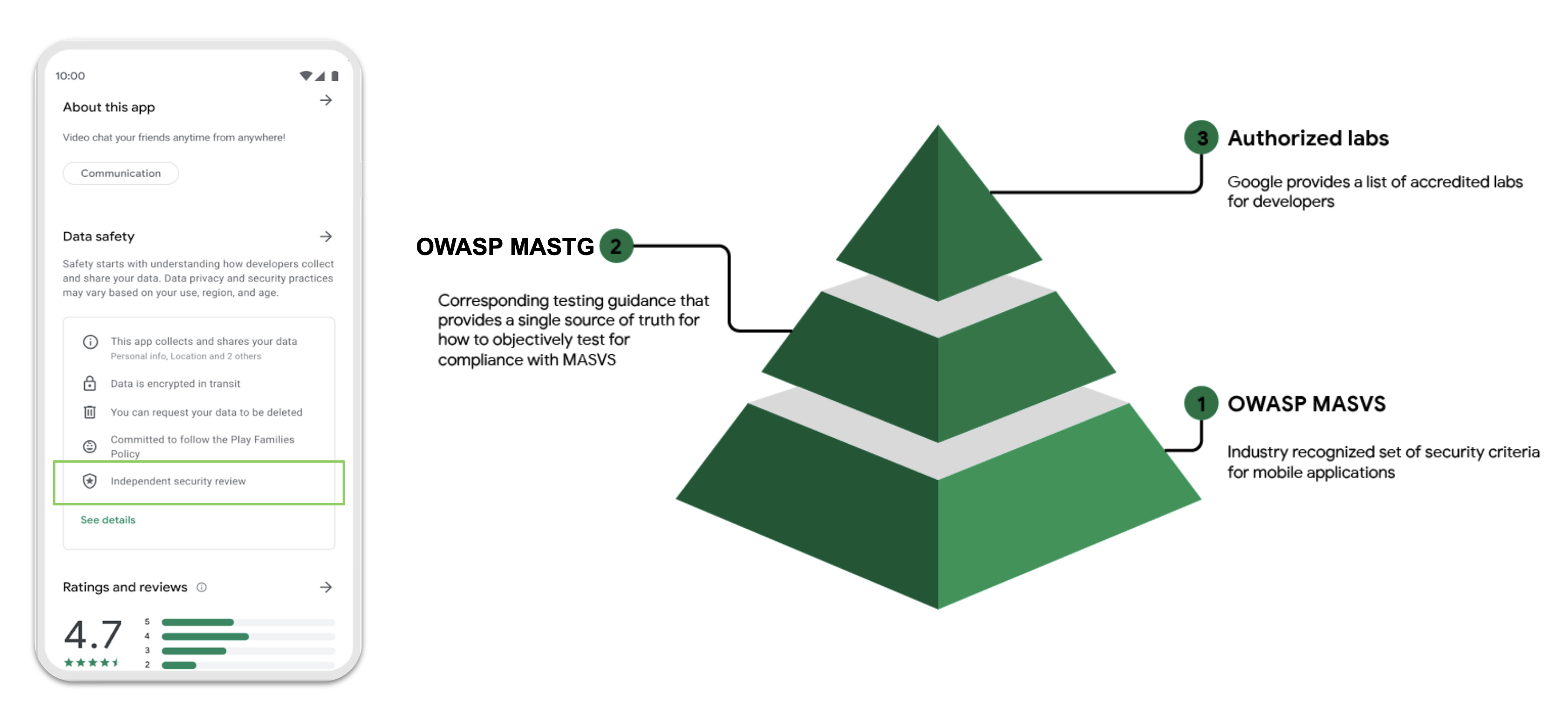

Google ADA MASA program

Performing regular security testing can help developers identify key vulnerabilities in their apps. Google Play will allow developers who have completed independent security validation to showcase this on their Data safety section. This helps users feel more confident about an app’s commitment to security and privacy.

In order to provide more transparency into the app’s security architecture, Google has introduced the MASA (Mobile Application Security Assessment) program as part of the App Defense Alliance (ADA). With MASA, Google has acknowledged the importance of leveraging a globally recognized standard for mobile app security to the mobile app ecosystem. Developers can work directly with an Authorized Lab partner to initiate a security assessment. Google will recognize developers who have had their applications independently validated against a set of MASVS Level 1 requirements and will showcase this on their Data safety section.

If you are a developer and would like to participate, you should complete this form.

Note that the limited nature of testing does not guarantee complete safety of the application. This independent review may not be scoped to verify the accuracy and completeness of a developer’s Data safety declarations. Developers remain solely responsible for making complete and accurate declarations in their app’s Play store listing.

How this Relates to Testing Other MASVS Categories

The following is a list of common privacy violations that you as a security tester should report (although not an exhaustive list):

- Example 1: An app that accesses a user’s inventory of installed apps and doesn’t treat this data as personal or sensitive data by sending it over the network (violating MSTG-STORAGE-4) or to another app via IPC mechanisms (violating MSTG-STORAGE-6).

- Example 2: An app displays sensitive data such as credit card details or user passwords without user authorization e.g. biometrics (violating MSTG-AUTH-10).

- Example 3: An app that accesses a user’s phone or contact book data and doesn’t treat this data as personal or sensitive data, additionally sending it over an unsecured network connection (violating MSTG-NETWORK-1).

- Example 4: An app collects device location (which is apparently not required for its proper functioning) and does not have a prominent disclosure explaining which feature uses this data (violating MSTG-PLATFORM-1).

You can find more common violations in Google Play Console Help (Policy Centre -> Privacy, deception and device abuse -> User data).

As you can see this is deeply related to other testing categories. When you’re testing them you’re often indirectly testing for User Privacy Protection. Keep this in mind since it will help you provide better and more comprehensive reports. Often you’ll also be able to reuse evidence from other tests in order to test for User Privacy Protection (see an example of this in “Testing User Education”).

Learn More

You can learn more about this and other privacy related topics here:

- iOS App Privacy Policy

- iOS Privacy Details Section on the App Store

- iOS Privacy Best Practices

- Android App Privacy Policy

- Android Data Safety Section on Google Play

- Preparing your app for the new Data safety section in Google Play

- Android Privacy Best Practices

Testing User Education (MSTG-STORAGE-12)

Testing User Education on Data Privacy on the App Marketplace

At this point, we’re only interested in knowing which privacy-related information is being disclosed by the developers and trying to evaluate if it seems reasonable (similarly as you’d do when testing for permissions).

It’s possible that the developers are not declaring certain information that is indeed being collected and\/or shared, but that’s a topic for a different test extending this one here. As part of this test, you are not supposed to provide privacy violation assurance.

Static Analysis

You can follow these steps:

- Search for the app in the corresponding app marketplace (e.g. Google Play, App Store).

- Go to the section “Privacy Details” (App Store) or “Safety Section” (Google Play).

- Verify if there’s any information available at all.

The test passes if the developer has complied with the app marketplace guidelines and included the required labels and explanations. Store and provide the information you got from the app marketplace as evidence, so that you can later use it to evaluate potential violations of privacy or data protection.

Dynamic analysis

As an optional step, you can also provide some kind of evidence as part of this test. For instance, if you’re testing an iOS app you can easily enable app activity recording and export a Privacy Report containing detailed app access to different resources such as photos, contacts, camera, microphone, network connections, etc.

Doing this has actually many advantages for testing other MASVS categories. It provides very useful information that you can use to test network communication in MASVS-NETWORK or when testing app permissions in MASVS-PLATFORM. While testing these other categories you might have taken similar measurements using other testing tools. You can also provide this as evidence for this test.

Ideally, the information available should be compared against what the app is actually meant to do. However, that’s far from a trivial task that could take from several days to weeks to complete depending on your resources and support from automated tooling. It also heavily depends on the app functionality and context and should be ideally performed on a white box setup working very closely with the app developers.

Testing User Education on Security Best Practices

Testing this might be especially challenging if you intend to automate it. We recommend using the app extensively and try to answer the following questions whenever applicable:

Fingerprint usage: when fingerprints are used for authentication providing access to high-risk transactions/information,

does the app inform the user about potential issues when having multiple fingerprints of other people registered to the device as well?

Rooting/Jailbreaking: when root or jailbreak detection is implemented,

does the app inform the user of the fact that certain high-risk actions will carry additional risk due to the jailbroken/rooted status of the device?

Specific credentials: when a user gets a recovery code, a password or a pin from the application (or sets one),

does the app instruct the user to never share this with anyone else and that only the app will request it?

Application distribution: in case of a high-risk application and in order to prevent users from downloading compromised versions of the application,

does the app manufacturer properly communicate the official way of distributing the app (e.g. from Google Play or the App Store)?

Prominent Disclosure: in any case,

does the app display prominent disclosure of data access, collection, use, and sharing? e.g. does the app use the App Tracking Transparency Framework to ask for the permission on iOS?

References

- Open-Source Licenses and Android - https://www.bignerdranch.com/blog/open-source-licenses-and-android/

- Software Licenses in Plain English - https://tldrlegal.com/

- Apple Human Interface Guidelines - https://developer.apple.com/design/human-interface-guidelines/ios/app-architecture/requesting-permission/

- Android App permissions best practices - https://developer.android.com/training/permissions/requesting.html#explain

OWASP MASVS

- MSTG-STORAGE-12: “The app educates the user about the types of personally identifiable information processed, as well as security best practices the user should follow in using the app.”