iOS Platform APIs

Testing App Permissions (MSTG-PLATFORM-1)

Overview

In contrast to Android, where each app runs on its own user ID, iOS makes all third-party apps run under the non-privileged mobile user. Each app has a unique home directory and is sandboxed, so that they cannot access protected system resources or files stored by the system or by other apps. These restrictions are implemented via sandbox policies (aka. profiles), which are enforced by the Trusted BSD (MAC) Mandatory Access Control Framework via a kernel extension. iOS applies a generic sandbox profile to all third-party apps called container. Access to protected resources or data (some also known as app capabilities) is possible, but it’s strictly controlled via special permissions known as entitlements.

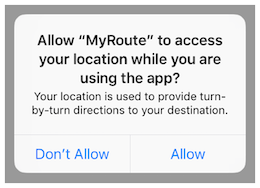

Some permissions can be configured by the app’s developers (e.g. Data Protection or Keychain Sharing) and will directly take effect after the installation. However, for others, the user will be explicitly asked the first time the app attempts to access a protected resource, for example:

- Bluetooth peripherals

- Calendar data

- Camera

- Contacts

- Health sharing

- Health updating

- HomeKit

- Location

- Microphone

- Motion

- Music and the media library

- Photos

- Reminders

- Siri

- Speech recognition

- the TV provider

Even though Apple urges to protect the privacy of the user and to be very clear on how to ask permissions, it can still be the case that an app requests too many of them for non-obvious reasons.

Some permissions such as Camera, Photos, Calendar Data, Motion, Contacts or Speech Recognition should be pretty straightforward to verify as it should be obvious if the app requires them to fulfill its tasks. Let’s consider the following examples ragarding the Photos permission, which, if granted, gives the app access to all user photos in the “Camera Roll” (the iOS default system-wide location for storing photos):

- The typical QR Code scanning app obviously requires the camera to function but might be requesting the photos permission as well. If storage is explicitly required, and depending on the sensitivity of the pictures being taken, these apps might better opt to use the app sandbox storage to avoid other apps (having the photos permission) to access them. See the chapter “Data Storage on iOS” for more information reagarding storage of sensitive data.

- Some apps require photo uploads (e.g. for profile pictures). Recent versions of iOS introduce new APIs such as

UIImagePickerController(iOS 11+) and its modern replacementPHPickerViewController(iOS 14+). These APIs run on a separate process from your app and by using them, the app gets read-only access exclusively to the images selected by the user instead of to the whole “Camera Roll”. This is considered a best practice to avoid requesting unnecessary permissions.

Other permissions like Bluetooth or Location require deeper verification steps. They may be required for the app to properly function but the data being handled by those tasks might not be properly protected. For more information and some examples please refer to the “Source Code Inspection” in the “Static Analysis” section below and to the “Dynamic Analysis” section.

When collecting or simply handling (e.g. caching) sensitive data, an app should provide proper mechanisms to give the user control over it, e.g. to be able to revoke access or to delete it. However, sensitive data might not only be stored or cached but also sent over the network. In both cases, it has to be ensured that the app properly follows the appropriate best practices, which in this case involve implementing proper data protection and transport security. More information on how to protect this kind of data can be found in the chapter “Network APIs”.

As you can see, using app capabilities and permissions mostly involve handling personal data, therefore being a matter of protecting the user’s privacy. See the articles “Protecting the User’s Privacy” and “Accessing Protected Resources” in Apple Developer Documentation for more details.

Device Capabilities

Device capabilities are used by the App Store to ensure that only compatible devices are listed and therefore are allowed to download the app. They are specified in the Info.plist file of the app under the UIRequiredDeviceCapabilities key.

<key>UIRequiredDeviceCapabilities</key>

<array>

<string>armv7</string>

</array>

Typically you’ll find the

armv7capability, meaning that the app is compiled only for the armv7 instruction set, or if it’s a 32/64-bit universal app.

For example, an app might be completely dependent on NFC to work (e.g. a “NFC Tag Reader” app). According to the archived iOS Device Compatibility Reference, NFC is only available starting on the iPhone 7 (and iOS 11). A developer might want to exclude all incompatible devices by setting the nfc device capability.

Regarding testing, you can consider UIRequiredDeviceCapabilities as a mere indication that the app is using some specific resources. Unlike the entitlements related to app capabilities, device capabilities do not confer any right or access to protected resources. Additional configuration steps might be required for that, which are very specific to each capability.

For example, if BLE is a core feature of the app, Apple’s Core Bluetooth Programming Guide explains the different things to be considered:

- The

bluetooth-ledevice capability can be set in order to restrict non-BLE capable devices from downloading their app. - App capabilities like

bluetooth-peripheralorbluetooth-central(bothUIBackgroundModes) should be added if BLE background processing is required.

However, this is not yet enough for the app to get access to the Bluetooth peripheral, the NSBluetoothPeripheralUsageDescription key has to be included in the Info.plist file, meaning that the user has to actively give permission. See “Purpose Strings in the Info.plist File” below for more information.

Entitlements

According to Apple’s iOS Security Guide:

Entitlements are key value pairs that are signed in to an app and allow authentication beyond runtime factors, like UNIX user ID. Since entitlements are digitally signed, they can’t be changed. Entitlements are used extensively by system apps and daemons to perform specific privileged operations that would otherwise require the process to run as root. This greatly reduces the potential for privilege escalation by a compromised system app or daemon.

Many entitlements can be set using the “Summary” tab of the Xcode target editor. Other entitlements require editing a target’s entitlements property list file or are inherited from the iOS provisioning profile used to run the app.

- Entitlements embedded in a provisioning profile that is used to code sign the app, which are composed of:

- Capabilities defined on the Xcode project’s target Capabilities tab, and/or:

- Enabled Services on the app’s App ID which are configured on the Identifiers section of the Certificates, ID’s and Profiles website.

- Other entitlements that are injected by the profile generation service.

- Entitlements from a code signing entitlements file.

- The app’s signature.

- The app’s embedded provisioning profile.

The Apple Developer Documentation also explains:

- During code signing, the entitlements corresponding to the app’s enabled Capabilities/Services are transferred to the app’s signature from the provisioning profile Xcode chose to sign the app.

- The provisioning profile is embedded into the app bundle during the build (

embedded.mobileprovision). - Entitlements from the “Code Signing Entitlements” section in Xcode’s “Build Settings” tab are transferred to the app’s signature.

For example, if you want to set the “Default Data Protection” capability, you would need to go to the Capabilities tab in Xcode and enable Data Protection. This is directly written by Xcode to the <appname>.entitlements file as the com.apple.developer.default-data-protection entitlement with default value NSFileProtectionComplete. In the IPA we might find this in the embedded.mobileprovision as:

<key>Entitlements</key>

<dict>

...

<key>com.apple.developer.default-data-protection</key>

<string>NSFileProtectionComplete</string>

</dict>

For other capabilities such as HealthKit, the user has to be asked for permission, therefore it is not enough to add the entitlements, special keys and strings have to be added to the Info.plist file of the app.

The following sections go more into detail about the mentioned files and how to perform static and dynamic analysis using them.

Static Analysis

Since iOS 10, these are the main areas which you need to inspect for permissions:

- Purpose Strings in the Info.plist File

- Code Signing Entitlements File

- Embedded Provisioning Profile File

- Entitlements Embedded in the Compiled App Binary

- Source Code Inspection

Purpose Strings in the Info.plist File

Purpose strings or usage description strings are custom texts that are offered to users in the system’s permission request alert when requesting permission to access protected data or resources.

If linking on or after iOS 10, developers are required to include purpose strings in their app’s Info.plist file. Otherwise, if the app attempts to access protected data or resources without having provided the corresponding purpose string, the access will fail and the app might even crash.

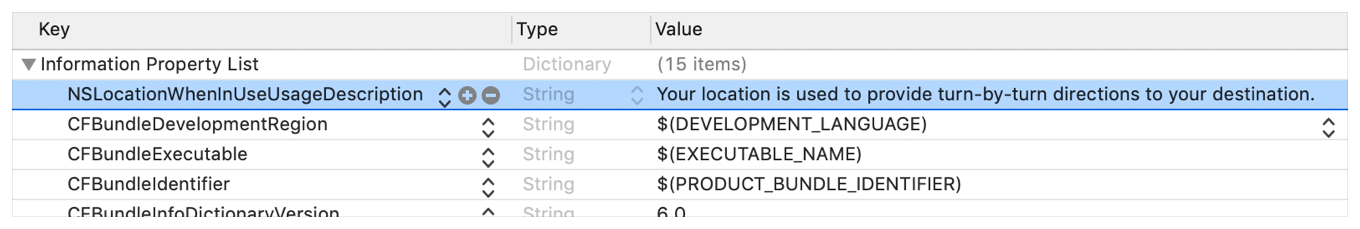

If having the original source code, you can verify the permissions included in the Info.plist file:

- Open the project with Xcode.

- Find and open the

Info.plistfile in the default editor and search for the keys starting with"Privacy -".

You may switch the view to display the raw values by right-clicking and selecting “Show Raw Keys/Values” (this way for example "Privacy - Location When In Use Usage Description" will turn into NSLocationWhenInUseUsageDescription).

If only having the IPA:

- Unzip the IPA.

- The

Info.plistis located inPayload/<appname>.app/Info.plist. - Convert it if needed (e.g.

plutil -convert xml1 Info.plist) as explained in the chapter “iOS Basic Security Testing”, section “The Info.plist File”. Inspect all purpose strings Info.plist keys, usually ending with

UsageDescription:xml <plist version="1.0"> <dict> <key>NSLocationWhenInUseUsageDescription</key> <string>Your location is used to provide turn-by-turn directions to your destination.</string>

For an overview of the different purpose strings Info.plist keys available see Table 1-2 at the Apple App Programming Guide for iOS. Click on the provided links to see the full description of each key in the CocoaKeys reference.

Following these guidelines should make it relatively simple to evaluate each and every entry in the Info.plist file to check if the permission makes sense.

For example, imagine the following lines were extracted from a Info.plist file used by a Solitaire game:

<key>NSHealthClinicalHealthRecordsShareUsageDescription</key>

<string>Share your health data with us!</string>

<key>NSCameraUsageDescription</key>

<string>We want to access your camera</string>

It should be suspicious that a regular solitaire game requests this kind of resource access as it probably does not have any need for accessing the camera nor a user’s health-records.

Apart from simply checking if the permissions make sense, further analysis steps might be derived from analyzing purpose strings e.g. if they are related to storage sensitive data. For example, NSPhotoLibraryUsageDescription can be considered as a storage permission giving access to files that are outside of the app’s sandbox and might also be accessible by other apps. In this case, it should be tested that no sensitive data is being stored there (photos in this case). For other purpose strings like NSLocationAlwaysUsageDescription, it must be also considered if the app is storing this data securely. Refer to the “Testing Data Storage” chapter for more information and best practices on securely storing sensitive data.

Code Signing Entitlements File

Certain capabilities require a code signing entitlements file (<appname>.entitlements). It is automatically generated by Xcode but may be manually edited and/or extended by the developer as well.

Here is an example of entitlements file of the open source app Telegram including the App Groups entitlement (application-groups):

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

...

<key>com.apple.security.application-groups</key>

<array>

<string>group.ph.telegra.Telegraph</string>

</array>

</dict>

...

</plist>

The entitlement outlined above does not require any additional permissions from the user. However, it is always a good practice to check all entitlements, as the app might overask the user in terms of permissions and thereby leak information.

As documented at Apple Developer Documentation, the App Groups entitlement is required to share information between different apps through IPC or a shared file container, which means that data can be shared on the device directly between the apps. This entitlement is also required if an app extension requires to share information with its containing app.

Depending on the data to-be-shared it might be more appropriate to share it using another method such as through a backend where this data could be potentially verified, avoiding tampering by e.g. the user himself.

Embedded Provisioning Profile File

When you do not have the original source code, you should analyze the IPA and search inside for the embedded provisioning profile that is usually located in the root app bundle folder (Payload/<appname>.app/) under the name embedded.mobileprovision.

This file is not a .plist, it is encoded using Cryptographic Message Syntax. On macOS you can inspect an embedded provisioning profile’s entitlements using the following command:

$ security cms -D -i embedded.mobileprovision

and then search for the Entitlements key region (<key>Entitlements</key>).

Entitlements Embedded in the Compiled App Binary

If you only have the app’s IPA or simply the installed app on a jailbroken device, you normally won’t be able to find .entitlements files. This could be also the case for the embedded.mobileprovision file. Still, you should be able to extract the entitlements property lists from the app binary yourself (which you’ve previously obtained as explained in the “iOS Basic Security Testing” chapter, section “Acquiring the App Binary”).

The following steps should work even when targeting an encrypted binary. If for some reason they don’t, you’ll have to decrypt and extract the app with e.g. Clutch (if compatible with your iOS version), frida-ios-dump or similar.

Extracting the Entitlements Plist from the App Binary

If you have the app binary in your computer, one approach is to use binwalk to extract (-e) all XML files (-y=xml):

$ binwalk -e -y=xml ./Telegram\ X

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1430180 0x15D2A4 XML document, version: "1.0"

1458814 0x16427E XML document, version: "1.0"

Or you can use radare2 (-qc to quietly run one command and exit) to search all strings on the app binary (izz) containing “PropertyList” (~PropertyList):

$ r2 -qc 'izz~PropertyList' ./Telegram\ X

0x0015d2a4 ascii <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="yes"?>\n<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC

"-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">\n<plist version="1.0">

...<key>com.apple.security.application-groups</key>\n\t\t<array>

\n\t\t\t<string>group.ph.telegra.Telegraph</string>...

0x0016427d ascii H<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>\n<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC

"-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">\n<plist version="1.0">\n

<dict>\n\t<key>cdhashes</key>...

In both cases (binwalk or radare2) we were able to extract the same two plist files. If we inspect the first one (0x0015d2a4) we see that we were able to completely recover the original entitlements file from Telegram.

Note: the

stringscommand will not help here as it will not be able to find this information. Better use grep with the-aflag directly on the binary or use radare2 (izz)/rabin2 (-zz).

If you access the app binary on the jailbroken device (e.g via SSH), you can use grep with the -a, --text flag (treats all files as ASCII text):

$ grep -a -A 5 'PropertyList' /var/containers/Bundle/Application/

15E6A58F-1CA7-44A4-A9E0-6CA85B65FA35/Telegram X.app/Telegram\ X

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>com.apple.security.application-groups</key>

<array>

...

Play with the -A num, --after-context=num flag to display more or less lines. You may use tools like the ones we presented above as well, if you have them also installed on your jailbroken iOS device.

This method should work even if the app binary is still encrypted (it was tested against several App Store apps).

Source Code Inspection

After having checked the <appname>.entitlements file and the Info.plist file, it is time to verify how the requested permissions and assigned capabilities are put to use. For this, a source code review should be enough. However, if you don’t have the original source code, verifying the use of permissions might be specially challenging as you might need to reverse engineer the app, refer to the “Dynamic Analysis” for more details on how to proceed.

When doing a source code review, pay attention to:

- whether the purpose strings in the

Info.plistfile match the programmatic implementations. - whether the registered capabilities are used in such a way that no confidential information is leaking.

Users can grant or revoke authorization at any time via “Settings”, therefore apps normally check the authorization status of a feature before accessing it. This can be done by using dedicated APIs available for many system frameworks that provide access to protected resources.

You can use the Apple Developer Documentation as a starting point. For example:

- Bluetooth: the

stateproperty of theCBCentralManagerclass is used to check system-authorization status for using Bluetooth peripherals. Location: search for methods of

CLLocationManager, e.g.locationServicesEnabled.default func checkForLocationServices() { if CLLocationManager.locationServicesEnabled() { // Location services are available, so query the user’s location. } else { // Update your app’s UI to show that the location is unavailable. } }See Table1 in “Determining the Availability of Location Services” (Apple Developer Documentation) for a complete list.

Go through the application searching for usages of these APIs and check what happens to sensitive data that might be obtained from them. For example, it might be stored or transmitted over the network, if this is the case, proper data protection and transport security should be additionally verified.

Dynamic Analysis

With help of the static analysis you should already have a list of the included permissions and app capabilities in use. However, as mentioned in “Source Code Inspection”, spotting the sensitive data and APIs related to those permissions and app capabilities might be a challenging task when you don’t have the original source code. Dynamic analysis can help here getting inputs to iterate onto the static analysis.

Following an approach like the one presented below should help you spotting the mentioned sensitive data and APIs:

- Consider the list of permissions / capabilities identified in the static analysis (e.g.

NSLocationWhenInUseUsageDescription). - Map them to the dedicated APIs available for the corresponding system frameworks (e.g.

Core Location). You may use the Apple Developer Documentation for this. - Trace classes or specific methods of those APIs (e.g.

CLLocationManager), for example, usingfrida-trace. - Identify which methods are being really used by the app while accessing the related feature (e.g. “Share your location”).

- Get a backtrace for those methods and try to build a call graph.

Once all methods were identified, you might use this knowledge to reverse engineer the app and try to find out how the data is being handled. While doing that you might spot new methods involved in the process which you can again feed to step 3. above and keep iterating between static and dynamic analysis.

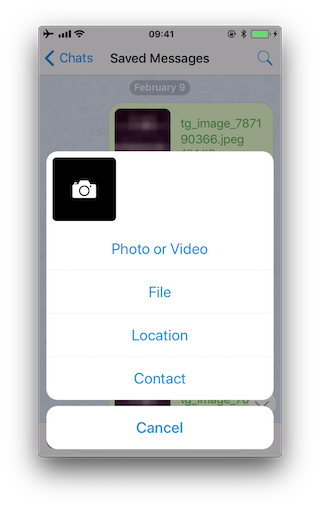

In the following example we use Telegram to open the share dialog from a chat and frida-trace to identify which methods are being called.

First we launch Telegram and start a trace for all methods matching the string “authorizationStatus” (this is a general approach because more classes apart from CLLocationManager implement this method):

$ frida-trace -U "Telegram" -m "*[* *authorizationStatus*]"

-Uconnects to the USB device.-mincludes an Objective-C method to the traces. You can use a glob pattern (e.g. with the “*” wildcard,-m "*[* *authorizationStatus*]"means “include any Objective-C method of any class containing ‘authorizationStatus’“). Typefrida-trace -hfor more information.

Now we open the share dialog:

The following methods are displayed:

1942 ms +[PHPhotoLibrary authorizationStatus]

1959 ms +[TGMediaAssetsLibrary authorizationStatusSignal]

1959 ms | +[TGMediaAssetsModernLibrary authorizationStatusSignal]

If we click on Location, another method will be traced:

11186 ms +[CLLocationManager authorizationStatus]

11186 ms | +[CLLocationManager _authorizationStatus]

11186 ms | | +[CLLocationManager _authorizationStatusForBundleIdentifier:0x0 bundle:0x0]

Use the auto-generated stubs of frida-trace to get more information like the return values and a backtrace. Do the following modifications to the JavaScript file below (the path is relative to the current directory):

// __handlers__/__CLLocationManager_authorizationStatus_.js

onEnter: function (log, args, state) {

log("+[CLLocationManager authorizationStatus]");

log("Called from:\n" +

Thread.backtrace(this.context, Backtracer.ACCURATE)

.map(DebugSymbol.fromAddress).join("\n\t") + "\n");

},

onLeave: function (log, retval, state) {

console.log('RET :' + retval.toString());

}

Clicking again on “Location” reveals more information:

3630 ms -[CLLocationManager init]

3630 ms | -[CLLocationManager initWithEffectiveBundleIdentifier:0x0 bundle:0x0]

3634 ms -[CLLocationManager setDelegate:0x14c9ab000]

3641 ms +[CLLocationManager authorizationStatus]

RET: 0x4

3641 ms Called from:

0x1031aa158 TelegramUI!+[TGLocationUtils requestWhenInUserLocationAuthorizationWithLocationManager:]

0x10337e2c0 TelegramUI!-[TGLocationPickerController initWithContext:intent:]

0x101ee93ac TelegramUI!0x1013ac

We see that +[CLLocationManager authorizationStatus] returned 0x4 (CLAuthorizationStatus.authorizedWhenInUse) and was called by +[TGLocationUtils requestWhenInUserLocationAuthorizationWithLocationManager:]. As we anticipated before, you might use this kind of information as an entry point when reverse engineering the app and from there get inputs (e.g. names of classes or methods) to keep feeding the dynamic analysis.

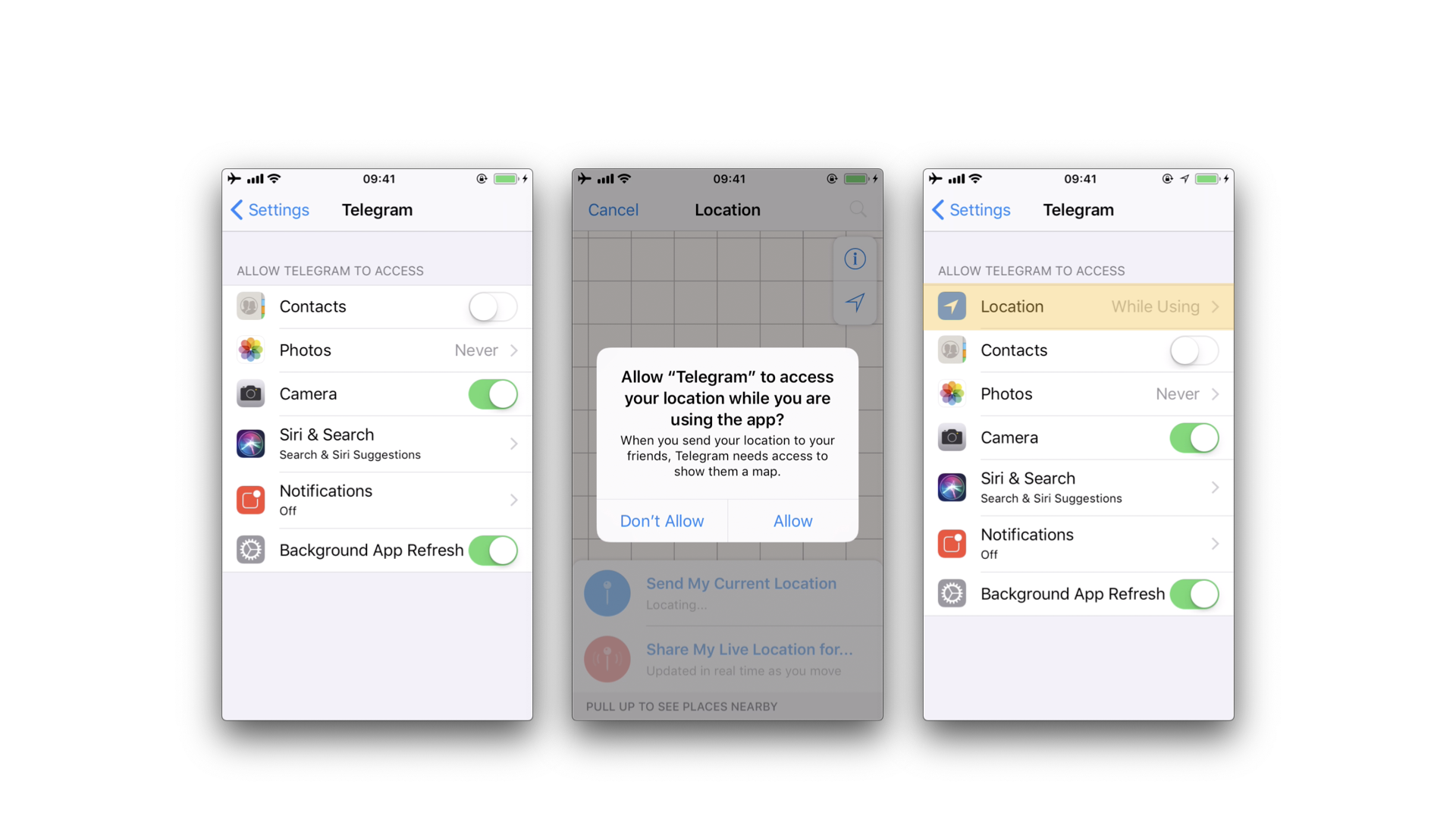

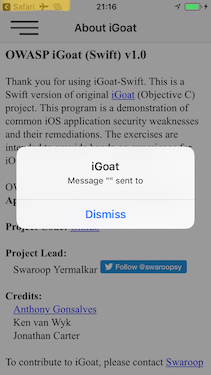

Next, there is a visual way to inspect the status of some app permissions when using the iPhone/iPad by opening “Settings” and scrolling down until you find the app you’re interested in. When clicking on it, this will open the “ALLOW APP_NAME TO ACCESS” screen. However, not all permissions might be displayed yet. You will have to trigger them in order to be listed on that screen.

For example, in the previous example, the “Location” entry was not being listed until we triggered the permission dialogue for the first time. Once we did it, no matter if we allowed the access or not, the the “Location” entry will be displayed.

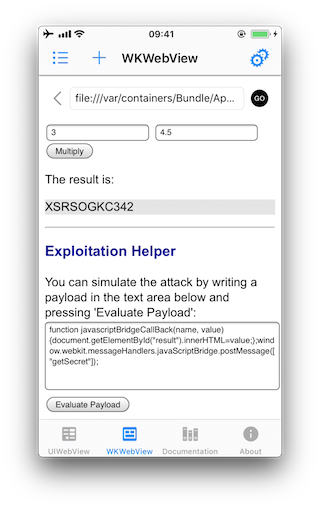

Testing for Sensitive Functionality Exposure Through IPC (MSTG-PLATFORM-4)

During implementation of a mobile application, developers may apply traditional techniques for IPC (such as using shared files or network sockets). The IPC system functionality offered by mobile application platforms should be used because it is much more mature than traditional techniques. Using IPC mechanisms with no security in mind may cause the application to leak or expose sensitive data.

In contrast to Android’s rich Inter-Process Communication (IPC) capability, iOS offers some rather limited options for communication between apps. In fact, there’s no way for apps to communicate directly. In this section we will present the different types of indirect communication offered by iOS and how to test them. Here’s an overview:

- Custom URL Schemes

- Universal Links

- UIActivity Sharing

- App Extensions

- UIPasteboard

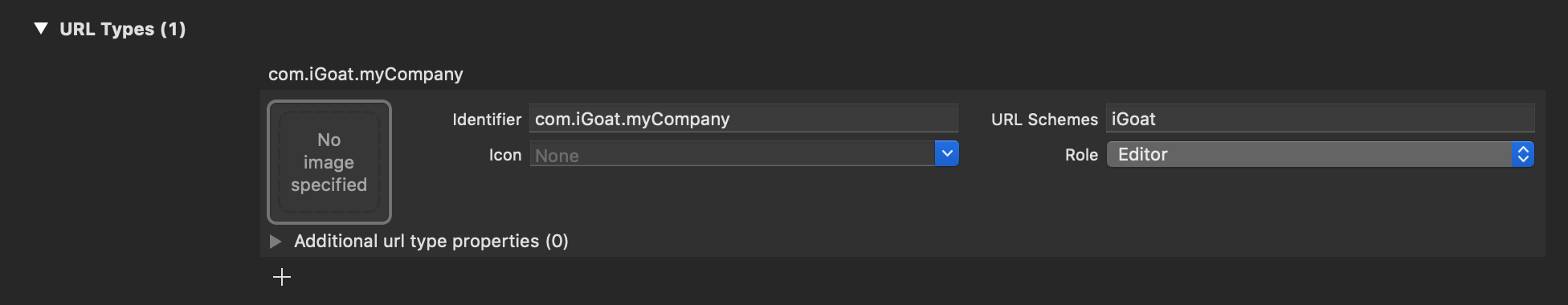

Custom URL Schemes

Please refer to the section “Testing Custom URL Schemes” for more information on what custom URL schemes are and how to test them.

Universal Links

Overview

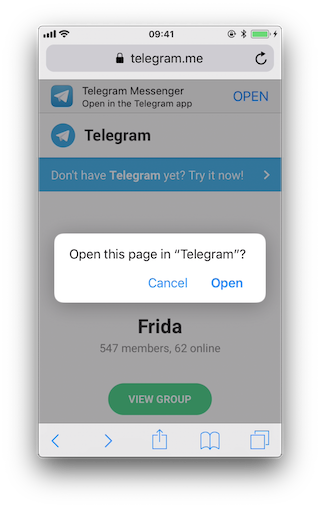

Universal links are the iOS equivalent to Android App Links (aka. Digital Asset Links) and are used for deep linking. When tapping a universal link (to the app’s website), the user will seamlessly be redirected to the corresponding installed app without going through Safari. If the app isn’t installed, the link will open in Safari.

Universal links are standard web links (HTTP/HTTPS) and are not to be confused with custom URL schemes, which originally were also used for deep linking.

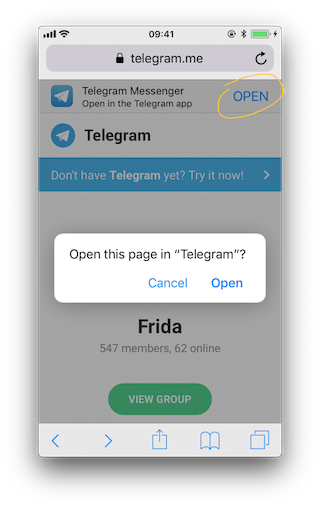

For example, the Telegram app supports both custom URL schemes and universal links:

tg://resolve?domain=fridadotreis a custom URL scheme and uses thetg://scheme.https://telegram.me/fridadotreis a universal link and uses thehttps://scheme.

Both result in the same action, the user will be redirected to the specified chat in Telegram (“fridadotre” in this case). However, universal links give several key benefits that are not applicable when using custom URL schemes and are the recommended way to implement deep linking, according to the Apple Developer Documentation. Specifically, universal links are:

- Unique: Unlike custom URL schemes, universal links can’t be claimed by other apps, because they use standard HTTP or HTTPS links to the app’s website. They were introduced as a way to prevent URL scheme hijacking attacks (an app installed after the original app may declare the same scheme and the system might target all new requests to the last installed app).

- Secure: When users install the app, iOS downloads and checks a file (the Apple App Site Association or AASA) that was uploaded to the web server to make sure that the website allows the app to open URLs on its behalf. Only the legitimate owners of the URL can upload this file, so the association of their website with the app is secure.

- Flexible: Universal links work even when the app is not installed. Tapping a link to the website would open the content in Safari, as users expect.

- Simple: One URL works for both the website and the app.

- Private: Other apps can communicate with the app without needing to know whether it is installed.

Static Analysis

Testing universal links on a static approach includes doing the following:

- Checking the Associated Domains entitlement

- Retrieving the Apple App Site Association file

- Checking the link receiver method

- Checking the data handler method

- Checking if the app is calling other app’s universal links

Checking the Associated Domains Entitlement

Universal links require the developer to add the Associated Domains entitlement and include in it a list of the domains that the app supports.

In Xcode, go to the Capabilities tab and search for Associated Domains. You can also inspect the .entitlements file looking for com.apple.developer.associated-domains. Each of the domains must be prefixed with applinks:, such as applinks:www.mywebsite.com.

Here’s an example from Telegram’s .entitlements file:

<key>com.apple.developer.associated-domains</key>

<array>

<string>applinks:telegram.me</string>

<string>applinks:t.me</string>

</array>

More detailed information can be found in the archived Apple Developer Documentation.

If you don’t have the original source code you can still search for them, as explained in “Entitlements Embedded in the Compiled App Binary”.

Retrieving the Apple App Site Association File

Try to retrieve the apple-app-site-association file from the server using the associated domains you got from the previous step. This file needs to be accessible via HTTPS, without any redirects, at https://<domain>/apple-app-site-association or https://<domain>/.well-known/apple-app-site-association.

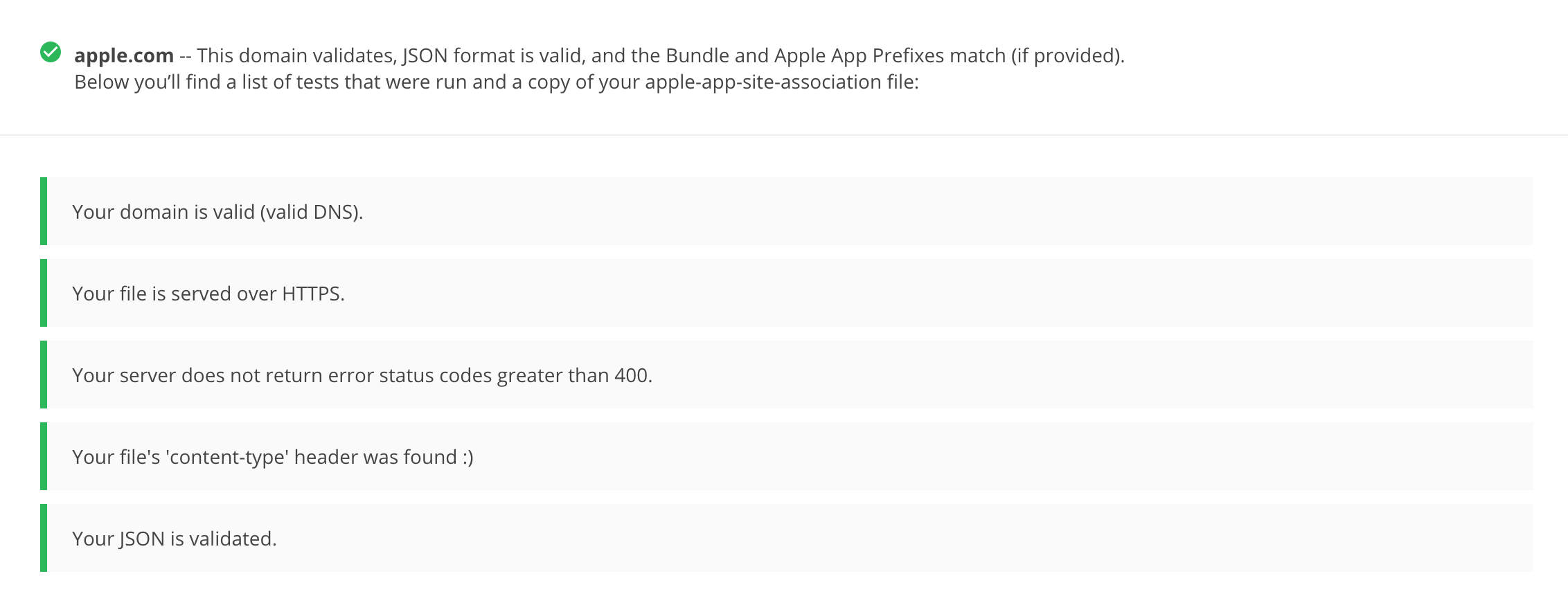

You can retrieve it yourself with your browser or use the Apple App Site Association (AASA) Validator. After entering the domain, it will display the file, verify it for you and show the results (e.g. if it is not being properly served over HTTPS). See the following example from apple.com:

{

"activitycontinuation": {

"apps": [

"W74U47NE8E.com.apple.store.Jolly"

]

},

"applinks": {

"apps": [],

"details": [

{

"appID": "W74U47NE8E.com.apple.store.Jolly",

"paths": [

"NOT /shop/buy-iphone/*",

"NOT /us/shop/buy-iphone/*",

"/xc/*",

"/shop/buy-*",

"/shop/product/*",

"/shop/bag/shared_bag/*",

"/shop/order/list",

"/today",

"/shop/watch/watch-accessories",

"/shop/watch/watch-accessories/*",

"/shop/watch/bands",

] } ] }

}

The “details” key inside “applinks” contains a JSON representation of an array that might contain one or more apps. The “appID” should match the “application-identifier” key from the app’s entitlements. Next, using the “paths” key, the developers can specify certain paths to be handled on a per app basis. Some apps, like Telegram use a standalone * ("paths": ["*"]) in order to allow all possible paths. Only if specific areas of the website should not be handled by some app, the developer can restrict access by excluding them by prepending a "NOT " (note the whitespace after the T) to the corresponding path. Also remember that the system will look for matches by following the order of the dictionaries in the array (first match wins).

This path exclusion mechanism is not to be seen as a security feature but rather as a filter that developer might use to specify which apps open which links. By default, iOS does not open any unverified links.

Remember that universal links verification occurs at installation time. iOS retrieves the AASA file for the declared domains (applinks) in its com.apple.developer.associated-domains entitlement. iOS will refuse to open those links if the verification did not succeed. Some reasons to fail verification might include:

- The AASA file is not served over HTTPS.

- The AASA is not available.

- The

appIDs do not match (this would be the case of a malicious app). iOS would successfully prevent any possible hijacking attacks.

Checking the Link Receiver Method

In order to receive links and handle them appropriately, the app delegate has to implement application:continueUserActivity:restorationHandler:. If you have the original project try searching for this method.

Please note that if the app uses openURL:options:completionHandler: to open a universal link to the app’s website, the link won’t open in the app. As the call originates from the app, it won’t be handled as a universal link.

From Apple Docs: When iOS launches your app after a user taps a universal link, you receive an

NSUserActivityobject with anactivityTypevalue ofNSUserActivityTypeBrowsingWeb. The activity object’swebpageURLproperty contains the URL that the user is accessing. The webpage URL property always contains an HTTP or HTTPS URL, and you can useNSURLComponentsAPIs to manipulate the components of the URL. […] To protect users’ privacy and security, you should not use HTTP when you need to transport data; instead, use a secure transport protocol such as HTTPS.

From the note above we can highlight that:

- The mentioned

NSUserActivityobject comes from thecontinueUserActivityparameter, as seen in the method above. - The scheme of the

webpageURLmust be HTTP or HTTPS (any other scheme should throw an exception). Theschemeinstance property ofURLComponents/NSURLComponentscan be used to verify this.

If you don’t have the original source code you can use radare2 or rabin2 to search the binary strings for the link receiver method:

$ rabin2 -zq Telegram\ X.app/Telegram\ X | grep restorationHan

0x1000deea9 53 52 application:continueUserActivity:restorationHandler:

Checking the Data Handler Method

You should check how the received data is validated. Apple explicitly warns about this:

Universal links offer a potential attack vector into your app, so make sure to validate all URL parameters and discard any malformed URLs. In addition, limit the available actions to those that do not risk the user’s data. For example, do not allow universal links to directly delete content or access sensitive information about the user. When testing your URL-handling code, make sure your test cases include improperly formatted URLs.

As stated in the Apple Developer Documentation, when iOS opens an app as the result of a universal link, the app receives an NSUserActivity object with an activityType value of NSUserActivityTypeBrowsingWeb. The activity object’s webpageURL property contains the HTTP or HTTPS URL that the user accesses. The following example in Swift verifies exactly this before opening the URL:

func application(_ application: UIApplication, continue userActivity: NSUserActivity,

restorationHandler: @escaping ([UIUserActivityRestoring]?) -> Void) -> Bool {

// ...

if userActivity.activityType == NSUserActivityTypeBrowsingWeb, let url = userActivity.webpageURL {

application.open(url, options: [:], completionHandler: nil)

}

return true

}

In addition, remember that if the URL includes parameters, they should not be trusted before being carefully sanitized and validated (even when coming from trusted domain). For example, they might have been spoofed by an attacker or might include malformed data. If that is the case, the whole URL and therefore the universal link request must be discarded.

The NSURLComponents API can be used to parse and manipulate the components of the URL. This can be also part of the method application:continueUserActivity:restorationHandler: itself or might occur on a separate method being called from it. The following example demonstrates this:

func application(_ application: UIApplication,

continue userActivity: NSUserActivity,

restorationHandler: @escaping ([Any]?) -> Void) -> Bool {

guard userActivity.activityType == NSUserActivityTypeBrowsingWeb,

let incomingURL = userActivity.webpageURL,

let components = NSURLComponents(url: incomingURL, resolvingAgainstBaseURL: true),

let path = components.path,

let params = components.queryItems else {

return false

}

if let albumName = params.first(where: { $0.name == "albumname" })?.value,

let photoIndex = params.first(where: { $0.name == "index" })?.value {

// Interact with album name and photo index

return true

} else {

// Handle when album and/or album name or photo index missing

return false

}

}

Finally, as stated above, be sure to verify that the actions triggered by the URL do not expose sensitive information or risk the user’s data on any way.

Checking if the App is Calling Other App’s Universal Links

An app might be calling other apps via universal links in order to simply trigger some actions or to transfer information, in that case, it should be verified that it is not leaking sensitive information.

If you have the original source code, you can search it for the openURL:options: completionHandler: method and check the data being handled.

Note that the

openURL:options:completionHandler:method is not only used to open universal links but also to call custom URL schemes.

This is an example from the Telegram app:

}, openUniversalUrl: { url, completion in

if #available(iOS 10.0, *) {

var parsedUrl = URL(string: url)

if let parsed = parsedUrl {

if parsed.scheme == nil || parsed.scheme!.isEmpty {

parsedUrl = URL(string: "https://\(url)")

}

}

if let parsedUrl = parsedUrl {

return UIApplication.shared.open(parsedUrl,

options: [UIApplicationOpenURLOptionUniversalLinksOnly: true as NSNumber],

completionHandler: { value in completion.completion(value)}

)

Note how the app adapts the scheme to “https” before opening it and how it uses the option UIApplicationOpenURLOptionUniversalLinksOnly: true that opens the URL only if the URL is a valid universal link and there is an installed app capable of opening that URL.

If you don’t have the original source code, search in the symbols and in the strings of the app binary. For example, we will search for Objective-C methods that contain “openURL”:

$ rabin2 -zq Telegram\ X.app/Telegram\ X | grep openURL

0x1000dee3f 50 49 application:openURL:sourceApplication:annotation:

0x1000dee71 29 28 application:openURL:options:

0x1000df2c9 9 8 openURL:

0x1000df772 35 34 openURL:options:completionHandler:

As expected, openURL:options:completionHandler: is among the ones found (remember that it might be also present because the app opens custom URL schemes). Next, to ensure that no sensitive information is being leaked you’ll have to perform dynamic analysis and inspect the data being transmitted. Please refer to “Identifying and Hooking the URL Handler Method” in the “Dynamic Analysis” of “Testing Custom URL Schemes” section for some examples on hooking and tracing this method.

Dynamic Analysis

If an app is implementing universal links, you should have the following outputs from the static analysis:

- the associated domains

- the Apple App Site Association file

- the link receiver method

- the data handler method

You can use this now to dynamically test them:

- Triggering universal links

- Identifying valid universal links

- Tracing the link receiver method

- Checking how the links are opened

Triggering Universal Links

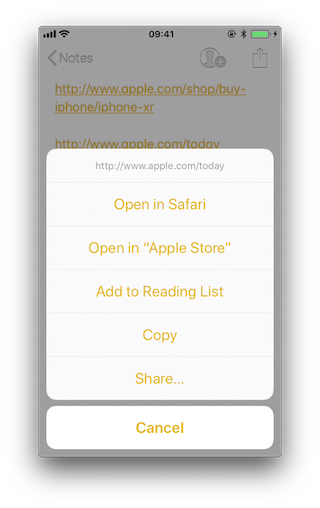

Unlike custom URL schemes, unfortunately you cannot test universal links from Safari just by typing them in the search bar directly as this is not allowed by Apple. But you can test them anytime using other apps like the Notes app:

- Open the Notes app and create a new note.

- Write the links including the domain.

- Leave the editing mode in the Notes app.

- Long press the links to open them (remember that a standard click triggers the default option).

To do it from Safari you will have to find an existing link on a website that once clicked, it will be recognized as a Universal Link. This can be a bit time consuming.

Alternatively you can also use Frida for this, see the section “Performing URL Requests” for more details.

Identifying Valid Universal Links

First of all we will see the difference between opening an allowed Universal Link and one that shouldn’t be allowed.

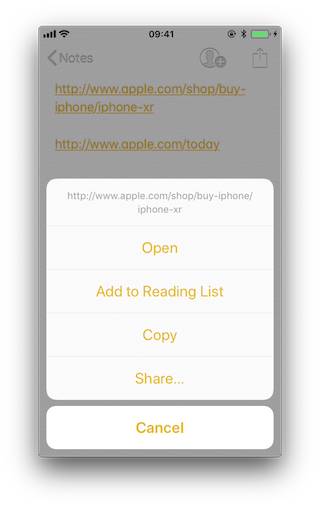

From the apple-app-site-association of apple.com we have seen above we chose the following paths:

"paths": [

"NOT /shop/buy-iphone/*",

...

"/today",

One of them should offer the “Open in app” option and the other should not.

If we long press on the first one (http://www.apple.com/shop/buy-iphone/iphone-xr) it only offers the option to open it (in the browser).

If we long press on the second (http://www.apple.com/today) it shows options to open it in Safari and in “Apple Store”:

Note that there is a difference between a click and a long press. Once we long press a link and select an option, e.g. “Open in Safari”, this will become the default option for all future clicks until we long press again and select another option.

If we repeat the process on the method application:continueUserActivity: restorationHandler: by either hooking or tracing, we will see how it gets called as soon as we open the allowed universal link. For this you can use for example frida-trace:

$ frida-trace -U "Apple Store" -m "*[* *restorationHandler*]"

Tracing the Link Receiver Method

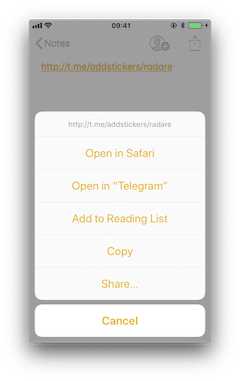

This section explains how to trace the link receiver method and how to extract additional information. For this example, we will use Telegram, as there are no restrictions in its apple-app-site-association file:

{

"applinks": {

"apps": [],

"details": [

{

"appID": "X834Q8SBVP.org.telegram.TelegramEnterprise",

"paths": [

"*"

]

},

{

"appID": "C67CF9S4VU.ph.telegra.Telegraph",

"paths": [

"*"

]

},

{

"appID": "X834Q8SBVP.org.telegram.Telegram-iOS",

"paths": [

"*"

]

}

]

}

}

In order to open the links we will also use the Notes app and frida-trace with the following pattern:

$ frida-trace -U Telegram -m "*[* *restorationHandler*]"

Write https://t.me/addstickers/radare (found through a quick Internet research) and open it from the Notes app.

First we let frida-trace generate the stubs in __handlers__/:

$ frida-trace -U Telegram -m "*[* *restorationHandler*]"

Instrumenting functions...

-[AppDelegate application:continueUserActivity:restorationHandler:]

You can see that only one function was found and is being instrumented. Trigger now the universal link and observe the traces.

298382 ms -[AppDelegate application:0x10556b3c0 continueUserActivity:0x1c4237780

restorationHandler:0x16f27a898]

You can observe that the function is in fact being called. You can now add code to the stubs in __handlers__/ to obtain more details:

// __handlers__/__AppDelegate_application_contin_8e36bbb1.js

onEnter: function (log, args, state) {

log("-[AppDelegate application: " + args[2] + " continueUserActivity: " + args[3] +

" restorationHandler: " + args[4] + "]");

log("\tapplication: " + ObjC.Object(args[2]).toString());

log("\tcontinueUserActivity: " + ObjC.Object(args[3]).toString());

log("\t\twebpageURL: " + ObjC.Object(args[3]).webpageURL().toString());

log("\t\tactivityType: " + ObjC.Object(args[3]).activityType().toString());

log("\t\tuserInfo: " + ObjC.Object(args[3]).userInfo().toString());

log("\trestorationHandler: " +ObjC.Object(args[4]).toString());

},

The new output is:

298382 ms -[AppDelegate application:0x10556b3c0 continueUserActivity:0x1c4237780

restorationHandler:0x16f27a898]

298382 ms application:<Application: 0x10556b3c0>

298382 ms continueUserActivity:<NSUserActivity: 0x1c4237780>

298382 ms webpageURL:http://t.me/addstickers/radare

298382 ms activityType:NSUserActivityTypeBrowsingWeb

298382 ms userInfo:{

}

298382 ms restorationHandler:<__NSStackBlock__: 0x16f27a898>

Apart from the function parameters we have added more information by calling some methods from them to get more details, in this case about the NSUserActivity. If we look in the Apple Developer Documentation we can see what else we can call from this object.

Checking How the Links Are Opened

If you want to know more about which function actually opens the URL and how the data is actually being handled you should keep investigating.

Extend the previous command in order to find out if there are any other functions involved into opening the URL.

$ frida-trace -U Telegram -m "*[* *restorationHandler*]" -i "*open*Url*"

-iincludes any method. You can also use a glob pattern here (e.g.-i "*open*Url*"means “include any function containing ‘open’, then ‘Url’ and something else”)

Again, we first let frida-trace generate the stubs in __handlers__/:

$ frida-trace -U Telegram -m "*[* *restorationHandler*]" -i "*open*Url*"

Instrumenting functions...

-[AppDelegate application:continueUserActivity:restorationHandler:]

$S10TelegramUI0A19ApplicationBindingsC16openUniversalUrlyySS_AA0ac4OpenG10Completion...

$S10TelegramUI15openExternalUrl7account7context3url05forceD016presentationData18application...

$S10TelegramUI31AuthorizationSequenceControllerC7account7strings7openUrl5apiId0J4HashAC0A4Core19...

...

Now you can see a long list of functions but we still don’t know which ones will be called. Trigger the universal link again and observe the traces.

/* TID 0x303 */

298382 ms -[AppDelegate application:0x10556b3c0 continueUserActivity:0x1c4237780

restorationHandler:0x16f27a898]

298619 ms | $S10TelegramUI15openExternalUrl7account7context3url05forceD016presentationData

18applicationContext20navigationController12dismissInputy0A4Core7AccountC_AA

14OpenURLContextOSSSbAA012PresentationK0CAA0a11ApplicationM0C7Display0

10NavigationO0CSgyyctF()

Apart from the Objective-C method, now there is one Swift function that is also of your interest.

There is probably no documentation for that Swift function but you can just demangle its symbol using swift-demangle via xcrun:

xcrun can be used invoke Xcode developer tools from the command-line, without having them in the path. In this case it will locate and run swift-demangle, an Xcode tool that demangles Swift symbols.

$ xcrun swift-demangle S10TelegramUI15openExternalUrl7account7context3url05forceD016presentationData

18applicationContext20navigationController12dismissInputy0A4Core7AccountC_AA14OpenURLContextOSSSbAA0

12PresentationK0CAA0a11ApplicationM0C7Display010NavigationO0CSgyyctF

Resulting in:

---> TelegramUI.openExternalUrl(

account: TelegramCore.Account, context: TelegramUI.OpenURLContext, url: Swift.String,

forceExternal: Swift.Bool, presentationData: TelegramUI.PresentationData,

applicationContext: TelegramUI.TelegramApplicationContext,

navigationController: Display.NavigationController?, dismissInput: () -> ()) -> ()

This not only gives you the class (or module) of the method, its name and the parameters but also reveals the parameter types and return type, so in case you need to dive deeper now you know where to start.

For now we will use this information to properly print the parameters by editing the stub file:

// __handlers__/TelegramUI/_S10TelegramUI15openExternalUrl7_b1a3234e.js

onEnter: function (log, args, state) {

log("TelegramUI.openExternalUrl(account: TelegramCore.Account,

context: TelegramUI.OpenURLContext, url: Swift.String, forceExternal: Swift.Bool,

presentationData: TelegramUI.PresentationData,

applicationContext: TelegramUI.TelegramApplicationContext,

navigationController: Display.NavigationController?, dismissInput: () -> ()) -> ()");

log("\taccount: " + ObjC.Object(args[0]).toString());

log("\tcontext: " + ObjC.Object(args[1]).toString());

log("\turl: " + ObjC.Object(args[2]).toString());

log("\tpresentationData: " + args[3]);

log("\tapplicationContext: " + ObjC.Object(args[4]).toString());

log("\tnavigationController: " + ObjC.Object(args[5]).toString());

},

This way, the next time we run it we get a much more detailed output:

298382 ms -[AppDelegate application:0x10556b3c0 continueUserActivity:0x1c4237780

restorationHandler:0x16f27a898]

298382 ms application:<Application: 0x10556b3c0>

298382 ms continueUserActivity:<NSUserActivity: 0x1c4237780>

298382 ms webpageURL:http://t.me/addstickers/radare

298382 ms activityType:NSUserActivityTypeBrowsingWeb

298382 ms userInfo:{

}

298382 ms restorationHandler:<__NSStackBlock__: 0x16f27a898>

298619 ms | TelegramUI.openExternalUrl(account: TelegramCore.Account,

context: TelegramUI.OpenURLContext, url: Swift.String, forceExternal: Swift.Bool,

presentationData: TelegramUI.PresentationData, applicationContext:

TelegramUI.TelegramApplicationContext, navigationController: Display.NavigationController?,

dismissInput: () -> ()) -> ()

298619 ms | account: TelegramCore.Account

298619 ms | context: nil

298619 ms | url: http://t.me/addstickers/radare

298619 ms | presentationData: 0x1c4e40fd1

298619 ms | applicationContext: nil

298619 ms | navigationController: TelegramUI.PresentationData

There you can observe the following:

- It calls

application:continueUserActivity:restorationHandler:from the app delegate as expected. application:continueUserActivity:restorationHandler:handles the URL but does not open it, it callsTelegramUI.openExternalUrlfor that.- The URL being opened is

https://t.me/addstickers/radare.

You can now keep going and try to trace and verify how the data is being validated. For example, if you have two apps that communicate via universal links you can use this to see if the sending app is leaking sensitive data by hooking these methods in the receiving app. This is especially useful when you don’t have the source code as you will be able to retrieve the full URL that you wouldn’t see other way as it might be the result of clicking some button or triggering some functionality.

In some cases, you might find data in userInfo of the NSUserActivity object. In the previous case there was no data being transferred but it might be the case for other scenarios. To see this, be sure to hook the userInfo property or access it directly from the continueUserActivity object in your hook (e.g. by adding a line like this log("userInfo:" + ObjC.Object(args[3]).userInfo().toString());).

Final Notes about Universal Links and Handoff

Universal links and Apple’s Handoff feature are related:

- Both rely on the same method when receiving data:

application:continueUserActivity:restorationHandler:

- Like universal links, the Handoff’s Activity Continuation must be declared in the

com.apple.developer.associated-domainsentitlement and in the server’sapple-app-site-associationfile (in both cases via the keyword"activitycontinuation":). See “Retrieving the Apple App Site Association File” above for an example.

Actually, the previous example in “Checking How the Links Are Opened” is very similar to the “Web Browser-to-Native App Handoff” scenario described in the “Handoff Programming Guide”:

If the user is using a web browser on the originating device, and the receiving device is an iOS device with a native app that claims the domain portion of the

webpageURLproperty, then iOS launches the native app and sends it anNSUserActivityobject with anactivityTypevalue ofNSUserActivityTypeBrowsingWeb. ThewebpageURLproperty contains the URL the user was visiting, while theuserInfodictionary is empty.

In the detailed output above you can see that NSUserActivity object we’ve received meets exactly the mentioned points:

298382 ms -[AppDelegate application:0x10556b3c0 continueUserActivity:0x1c4237780

restorationHandler:0x16f27a898]

298382 ms application:<Application: 0x10556b3c0>

298382 ms continueUserActivity:<NSUserActivity: 0x1c4237780>

298382 ms webpageURL:http://t.me/addstickers/radare

298382 ms activityType:NSUserActivityTypeBrowsingWeb

298382 ms userInfo:{

}

298382 ms restorationHandler:<__NSStackBlock__: 0x16f27a898>

This knowledge should help you when testing apps supporting Handoff.

UIActivity Sharing

Overview

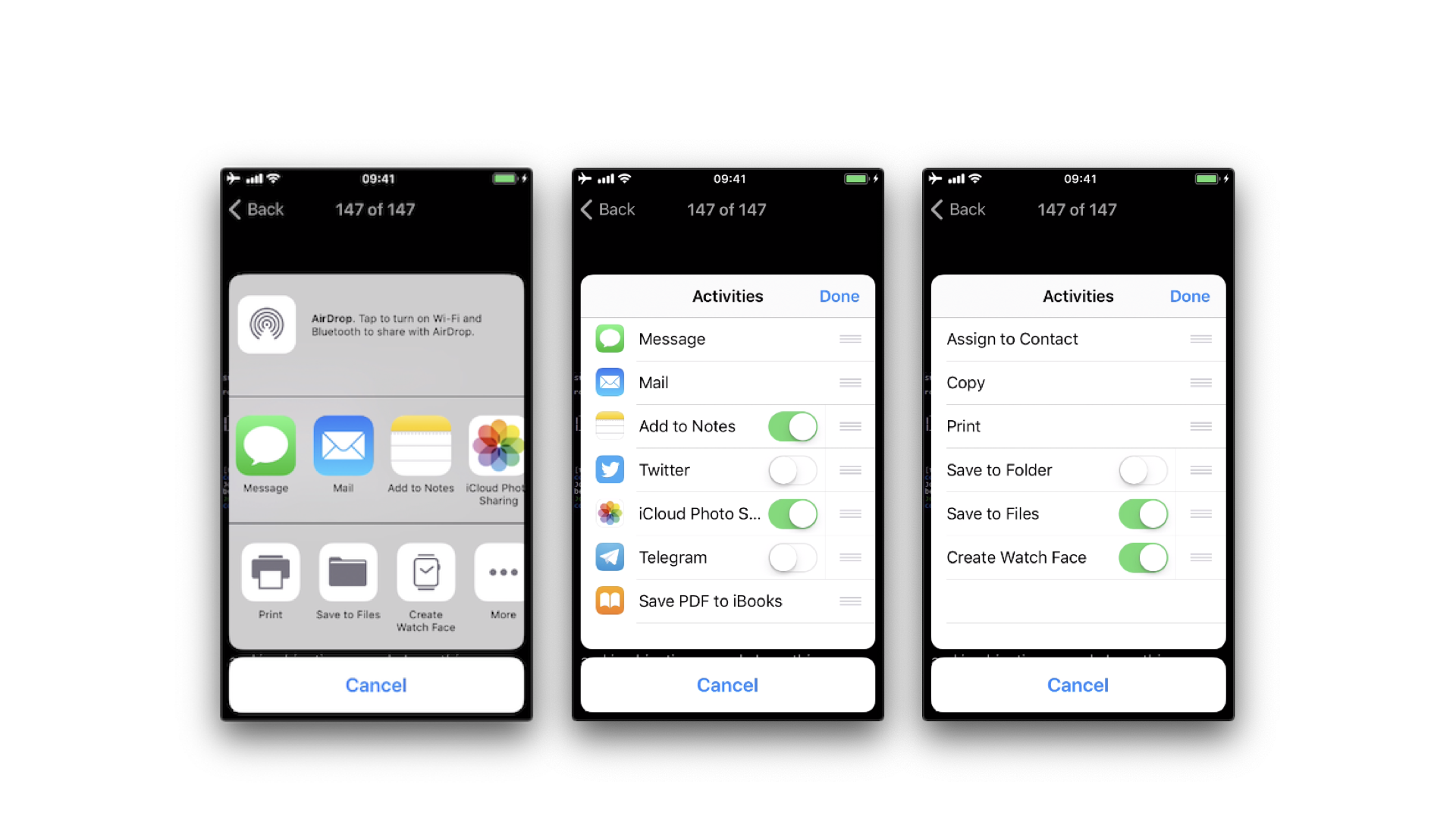

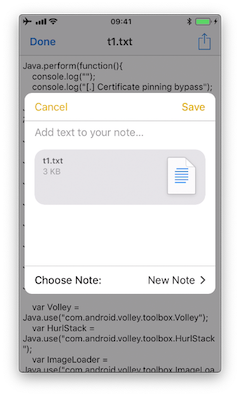

Starting on iOS 6 it is possible for third-party apps to share data (items) via specific mechanisms like AirDrop, for example. From a user perspective, this feature is the well-known system-wide share activity sheet that appears after clicking on the “Share” button.

The available built-in sharing mechanisms (aka. Activity Types) include:

- airDrop

- assignToContact

- copyToPasteboard

- message

- postToFacebook

- postToTwitter

A full list can be found in UIActivity.ActivityType. If not considered appropriate for the app, the developers have the possibility to exclude some of these sharing mechanisms.

Static Analysis

Sending Items

When testing UIActivity Sharing you should pay special attention to:

- the data (items) being shared,

- the custom activities,

- the excluded activity types.

Data sharing via UIActivity works by creating a UIActivityViewController and passing it the desired items (URLs, text, a picture) on init(activityItems: applicationActivities:).

As we mentioned before, it is possible to exclude some of the sharing mechanisms via the controller’s excludedActivityTypes property. It is highly recommended to do the tests using the latest versions of iOS as the number of activity types that can be excluded can increase. The developers have to be aware of this and explicitely exclude the ones that are not appropriate for the app data. Some activity types might not be even documented like “Create Watch Face”.

If having the source code, you should take a look at the UIActivityViewController:

- Inspect the activities passed to the

init(activityItems:applicationActivities:)method. - Check if it defines custom activities (also being passed to the previous method).

- Verify the

excludedActivityTypes, if any.

If you only have the compiled/installed app, try searching for the previous method and property, for example:

$ rabin2 -zq Telegram\ X.app/Telegram\ X | grep -i activityItems

0x1000df034 45 44 initWithActivityItems:applicationActivities:

Receiving Items

When receiving items, you should check:

- if the app declares custom document types by looking into Exported/Imported UTIs (“Info” tab of the Xcode project). The list of all system declared UTIs (Uniform Type Identifiers) can be found in the archived Apple Developer Documentation.

- if the app specifies any document types that it can open by looking into Document Types (“Info” tab of the Xcode project). If present, they consist of name and one or more UTIs that represent the data type (e.g. “public.png” for PNG files). iOS uses this to determine if the app is eligible to open a given document (specifying Exported/Imported UTIs is not enough).

- if the app properly verifies the received data by looking into the implementation of

application:openURL:options:(or its deprecated versionUIApplicationDelegate application:openURL:sourceApplication:annotation:) in the app delegate.

If not having the source code you can still take a look into the Info.plist file and search for:

UTExportedTypeDeclarations/UTImportedTypeDeclarationsif the app declares exported/imported custom document types.CFBundleDocumentTypesto see if the app specifies any document types that it can open.

A very complete explanation about the use of these keys can be found on Stackoverflow.

Let’s see a real-world example. We will take a File Manager app and take a look at these keys. We used objection here to read the Info.plist file.

objection --gadget SomeFileManager run ios plist cat Info.plist

Note that this is the same as if we would retrieve the IPA from the phone or accessed via e.g. SSH and navigated to the corresponding folder in the IPA / app sandbox. However, with objection we are just one command away from our goal and this can be still considered static analysis.

The first thing we noticed is that app does not declare any imported custom document types but we could find a couple of exported ones:

UTExportedTypeDeclarations = (

{

UTTypeConformsTo = (

"public.data"

);

UTTypeDescription = "SomeFileManager Files";

UTTypeIdentifier = "com.some.filemanager.custom";

UTTypeTagSpecification = {

"public.filename-extension" = (

ipa,

deb,

zip,

rar,

tar,

gz,

...

key,

pem,

p12,

cer

);

};

}

);

The app also declares the document types it opens as we can find the key CFBundleDocumentTypes:

CFBundleDocumentTypes = (

{

...

CFBundleTypeName = "SomeFileManager Files";

LSItemContentTypes = (

"public.content",

"public.data",

"public.archive",

"public.item",

"public.database",

"public.calendar-event",

...

);

}

);

We can see that this File Manager will try to open anything that conforms to any of the UTIs listed in LSItemContentTypes and it’s ready to open files with the extensions listed in UTTypeTagSpecification/"public.filename-extension". Please take a note of this because it will be useful if you want to search for vulnerabilities when dealing with the different types of files when performing dynamic analysis.

Dynamic Analysis

Sending Items

There are three main things you can easily inspect by performing dynamic instrumentation:

- The

activityItems: an array of the items being shared. They might be of different types, e.g. one string and one picture to be shared via a messaging app. - The

applicationActivities: an array ofUIActivityobjects representing the app’s custom services. - The

excludedActivityTypes: an array of the Activity Types that are not supported, e.g.postToFacebook.

To achieve this you can do two things:

- Hook the method we have seen in the static analysis (

init(activityItems: applicationActivities:)) to get theactivityItemsandapplicationActivities. - Find out the excluded activities by hooking

excludedActivityTypesproperty.

Let’s see an example using Telegram to share a picture and a text file. First prepare the hooks, we will use the Frida REPL and write a script for this:

Interceptor.attach(

ObjC.classes.

UIActivityViewController['- initWithActivityItems:applicationActivities:'].implementation, {

onEnter: function (args) {

printHeader(args)

this.initWithActivityItems = ObjC.Object(args[2]);

this.applicationActivities = ObjC.Object(args[3]);

console.log("initWithActivityItems: " + this.initWithActivityItems);

console.log("applicationActivities: " + this.applicationActivities);

},

onLeave: function (retval) {

printRet(retval);

}

});

Interceptor.attach(

ObjC.classes.UIActivityViewController['- excludedActivityTypes'].implementation, {

onEnter: function (args) {

printHeader(args)

},

onLeave: function (retval) {

printRet(retval);

}

});

function printHeader(args) {

console.log(Memory.readUtf8String(args[1]) + " @ " + args[1])

};

function printRet(retval) {

console.log('RET @ ' + retval + ': ' );

try {

console.log(new ObjC.Object(retval).toString());

} catch (e) {

console.log(retval.toString());

}

};

You can store this as a JavaScript file, e.g. inspect_send_activity_data.js and load it like this:

$ frida -U Telegram -l inspect_send_activity_data.js

Now observe the output when you first share a picture:

[*] initWithActivityItems:applicationActivities: @ 0x18c130c07

initWithActivityItems: (

"<UIImage: 0x1c4aa0b40> size {571, 264} orientation 0 scale 1.000000"

)

applicationActivities: nil

RET @ 0x13cb2b800:

<UIActivityViewController: 0x13cb2b800>

[*] excludedActivityTypes @ 0x18c0f8429

RET @ 0x0:

nil

and then a text file:

[*] initWithActivityItems:applicationActivities: @ 0x18c130c07

initWithActivityItems: (

"<QLActivityItemProvider: 0x1c4a30140>",

"<UIPrintInfo: 0x1c0699a50>"

)

applicationActivities: (

)

RET @ 0x13c4bdc00:

<_UIDICActivityViewController: 0x13c4bdc00>

[*] excludedActivityTypes @ 0x18c0f8429

RET @ 0x1c001b1d0:

(

"com.apple.UIKit.activity.MarkupAsPDF"

)

You can see that:

- For the picture, the activity item is a

UIImageand there are no excluded activities. - For the text file there are two different activity items and

com.apple.UIKit.activity. MarkupAsPDFis excluded.

In the previous example, there were no custom applicationActivities and only one excluded activity. However, to better illustrate what you can expect from other apps we have shared a picture using another app, here you can see a bunch of application activities and excluded activities (output was edited to hide the name of the originating app):

[*] initWithActivityItems:applicationActivities: @ 0x18c130c07

initWithActivityItems: (

"<SomeActivityItemProvider: 0x1c04bd580>"

)

applicationActivities: (

"<SomeActionItemActivityAdapter: 0x141de83b0>",

"<SomeActionItemActivityAdapter: 0x147971cf0>",

"<SomeOpenInSafariActivity: 0x1479f0030>",

"<SomeOpenInChromeActivity: 0x1c0c8a500>"

)

RET @ 0x142138a00:

<SomeActivityViewController: 0x142138a00>

[*] excludedActivityTypes @ 0x18c0f8429

RET @ 0x14797c3e0:

(

"com.apple.UIKit.activity.Print",

"com.apple.UIKit.activity.AssignToContact",

"com.apple.UIKit.activity.SaveToCameraRoll",

"com.apple.UIKit.activity.CopyToPasteboard",

)

Receiving Items

After performing the static analysis you would know the document types that the app can open and if it declares any custom document types and (part of) the methods involved. You can use this now to test the receiving part:

- Share a file with the app from another app or send it via AirDrop or e-mail. Choose the file so that it will trigger the “Open with…” dialogue (that is, there is no default app that will open the file, a PDF for example).

- Hook

application:openURL:options:and any other methods that were identified in a previous static analysis. - Observe the app behavior.

- In addition, you could send specific malformed files and/or use a fuzzing technique.

To illustrate this with an example we have chosen the same real-world file manager app from the static analysis section and followed these steps:

- Send a PDF file from another Apple device (e.g. a MacBook) via Airdrop.

- Wait for the AirDrop popup to appear and click on Accept.

As there is no default app that will open the file, it switches to the Open with… popup. There, we can select the app that will open our file. The next screenshot shows this (we have modified the display name using Frida to conceal the app’s real name):

After selecting SomeFileManager we can see the following:

bash (0x1c4077000) -[AppDelegate application:openURL:options:] application: <UIApplication: 0x101c00950> openURL: file:///var/mobile/Library/Application%20Support /Containers/com.some.filemanager/Documents/Inbox/OWASP_MASVS.pdf options: { UIApplicationOpenURLOptionsAnnotationKey = { LSMoveDocumentOnOpen = 1; }; UIApplicationOpenURLOptionsOpenInPlaceKey = 0; UIApplicationOpenURLOptionsSourceApplicationKey = "com.apple.sharingd"; "_UIApplicationOpenURLOptionsSourceProcessHandleKey" = "<FBSProcessHandle: 0x1c3a63140; sharingd:605; valid: YES>"; } 0x18c7930d8 UIKit!__58-[UIApplication _applicationOpenURLAction:payload:origin:]_block_invoke ... 0x1857cdc34 FrontBoardServices!-[FBSSerialQueue _performNextFromRunLoopSource] RET: 0x1

As you can see, the sending application is com.apple.sharingd and the URL’s scheme is file://. Note that once we select the app that should open the file, the system already moved the file to the corresponding destination, that is to the app’s Inbox. The apps are then responsible for deleting the files inside their Inboxes. This app, for example, moves the file to /var/mobile/Documents/ and removes it from the Inbox.

(0x1c002c760) -[XXFileManager moveItemAtPath:toPath:error:]

moveItemAtPath: /var/mobile/Library/Application Support/Containers

/com.some.filemanager/Documents/Inbox/OWASP_MASVS.pdf

toPath: /var/mobile/Documents/OWASP_MASVS (1).pdf

error: 0x16f095bf8

0x100f24e90 SomeFileManager!-[AppDelegate __handleOpenURL:]

0x100f25198 SomeFileManager!-[AppDelegate application:openURL:options:]

0x18c7930d8 UIKit!__58-[UIApplication _applicationOpenURLAction:payload:origin:]_block_invoke

...

0x1857cd9f4 FrontBoardServices!__FBSSERIALQUEUE_IS_CALLING_OUT_TO_A_BLOCK__

RET: 0x1

If you look at the stack trace, you can see how application:openURL:options: called __handleOpenURL:, which called moveItemAtPath:toPath:error:. Notice that we have now this information without having the source code for the target app. The first thing that we had to do was clear: hook application:openURL:options:. Regarding the rest, we had to think a little bit and come up with methods that we could start tracing and are related to the file manager, for example, all methods containing the strings “copy”, “move”, “remove”, etc. until we have found that the one being called was moveItemAtPath:toPath:error:.

A final thing worth noticing here is that this way of handling incoming files is the same for custom URL schemes. Please refer to the “Testing Custom URL Schemes” section for more information.

App Extensions

Overview

What are app extensions

Together with iOS 8, Apple introduced App Extensions. According to Apple App Extension Programming Guide, app extensions let apps offer custom functionality and content to users while they’re interacting with other apps or the system. In order to do this, they implement specific, well scoped tasks like, for example, define what happens after the user clicks on the “Share” button and selects some app or action, provide the content for a Today widget or enable a custom keyboard.

Depending on the task, the app extension will have a particular type (and only one), the so-called extension points. Some notable ones are:

- Custom Keyboard: replaces the iOS system keyboard with a custom keyboard for use in all apps.

- Share: post to a sharing website or share content with others.

- Today: also called widgets, they offer content or perform quick tasks in the Today view of Notification Center.

How do app extensions interact with other apps

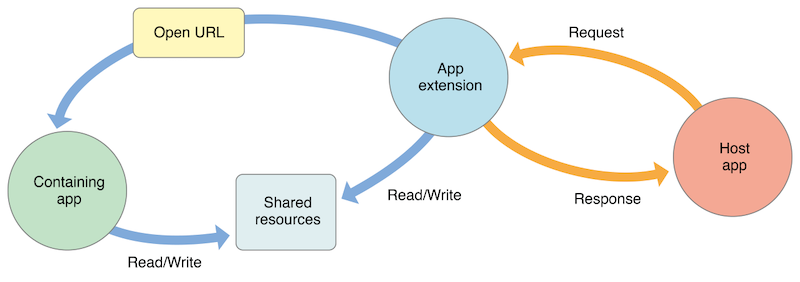

There are three important elements here:

- App extension: is the one bundled inside a containing app. Host apps interact with it.

- Host app: is the (third-party) app that triggers the app extension of another app.

- Containing app: is the app that contains the app extension bundled into it.

For example, the user selects text in the host app, clicks on the “Share” button and selects one “app” or action from the list. This triggers the app extension of the containing app. The app extension displays its view within the context of the host app and uses the items provided by the host app, the selected text in this case, to perform a specific task (post it on a social network, for example). See this picture from the Apple App Extension Programming Guide which pretty good summarizes this:

Security Considerations

From the security point of view it is important to note that:

- An app extension does never communicate directly with its containing app (typically, it isn’t even running while the contained app extension is running).

- An app extension and the host app communicate via inter-process communication.

- An app extension’s containing app and the host app don’t communicate at all.

- A Today widget (and no other app extension type) can ask the system to open its containing app by calling the

openURL:completionHandler:method of theNSExtensionContextclass. - Any app extension and its containing app can access shared data in a privately defined shared container.

In addition:

- App extensions cannot access some APIs, for example, HealthKit.

- They cannot receive data using AirDrop but do can send data.

- No long-running background tasks are allowed but uploads or downloads can be initiated.

- App extensions cannot access the camera or microphone on an iOS device (except for iMessage app extensions).

Static Analysis

The static analysis will take care of:

- Verifying if the app contains app extensions

- Determining the supported data types

- Checking data sharing with the containing app

- Verifying if the app restricts the use of app extensions

Verifying if the App Contains App Extensions

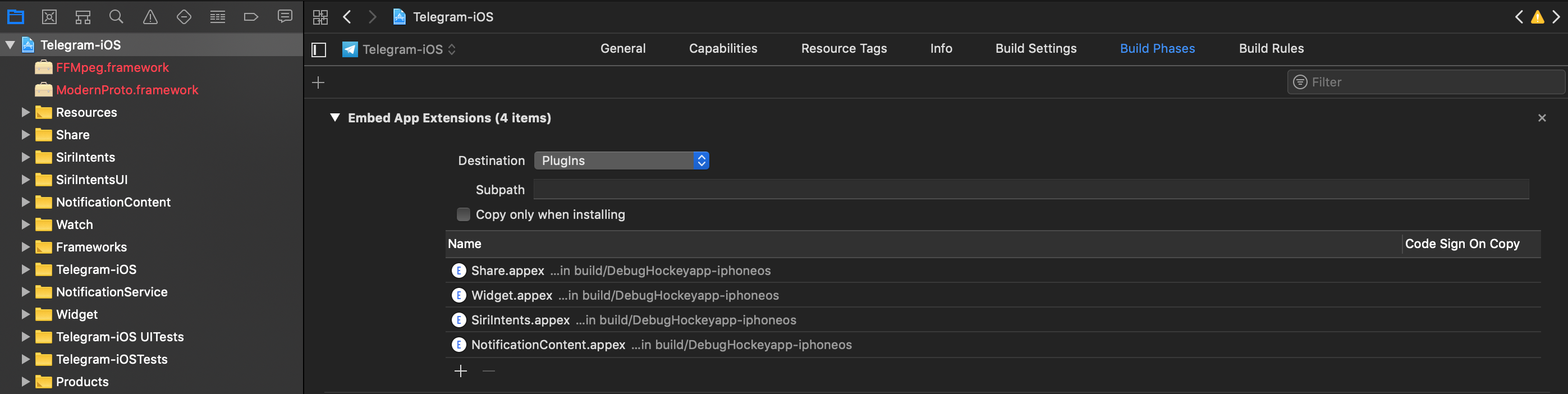

If you have the original source code you can search for all occurrences of NSExtensionPointIdentifier with Xcode (cmd+shift+f) or take a look into “Build Phases / Embed App extensions”:

There you can find the names of all embedded app extensions followed by .appex, now you can navigate to the individual app extensions in the project.

If not having the original source code:

Grep for NSExtensionPointIdentifier among all files inside the app bundle (IPA or installed app):

$ grep -nr NSExtensionPointIdentifier Payload/Telegram\ X.app/

Binary file Payload/Telegram X.app//PlugIns/SiriIntents.appex/Info.plist matches

Binary file Payload/Telegram X.app//PlugIns/Share.appex/Info.plist matches

Binary file Payload/Telegram X.app//PlugIns/NotificationContent.appex/Info.plist matches

Binary file Payload/Telegram X.app//PlugIns/Widget.appex/Info.plist matches

Binary file Payload/Telegram X.app//Watch/Watch.app/PlugIns/Watch Extension.appex/Info.plist matches

You can also access per SSH, find the app bundle and list all inside PlugIns (they are placed there by default) or do it with objection:

ph.telegra.Telegraph on (iPhone: 11.1.2) [usb] # cd PlugIns

/var/containers/Bundle/Application/15E6A58F-1CA7-44A4-A9E0-6CA85B65FA35/

Telegram X.app/PlugIns

ph.telegra.Telegraph on (iPhone: 11.1.2) [usb] # ls

NSFileType Perms NSFileProtection Read Write Name

------------ ------- ------------------ ------ ------- -------------------------

Directory 493 None True False NotificationContent.appex

Directory 493 None True False Widget.appex

Directory 493 None True False Share.appex

Directory 493 None True False SiriIntents.appex

We can see now the same four app extensions that we saw in Xcode before.

Determining the Supported Data Types

This is important for data being shared with host apps (e.g. via Share or Action Extensions). When the user selects some data type in a host app and it matches the data types define here, the host app will offer the extension. It is worth noticing the difference between this and data sharing via UIActivity where we had to define the document types, also using UTIs. An app does not need to have an extension for that. It is possible to share data using only UIActivity.

Inspect the app extension’s Info.plist file and search for NSExtensionActivationRule. That key specifies the data being supported as well as e.g. maximum of items supported. For example:

<key>NSExtensionAttributes</key>

<dict>

<key>NSExtensionActivationRule</key>

<dict>

<key>NSExtensionActivationSupportsImageWithMaxCount</key>

<integer>10</integer>

<key>NSExtensionActivationSupportsMovieWithMaxCount</key>

<integer>1</integer>

<key>NSExtensionActivationSupportsWebURLWithMaxCount</key>

<integer>1</integer>

</dict>

</dict>

Only the data types present here and not having 0 as MaxCount will be supported. However, more complex filtering is possible by using a so-called predicate string that will evaluate the UTIs given. Please refer to the Apple App Extension Programming Guide for more detailed information about this.

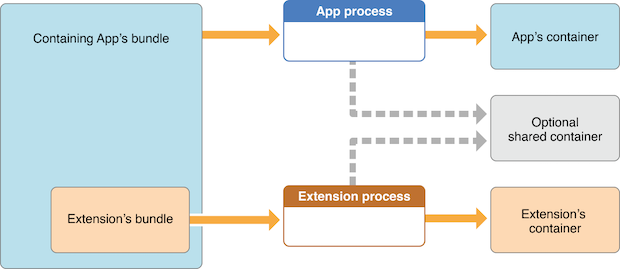

Checking Data Sharing with the Containing App

Remember that app extensions and their containing apps do not have direct access to each other’s containers. However, data sharing can be enabled. This is done via “App Groups” and the NSUserDefaults API. See this figure from Apple App Extension Programming Guide:

As also mentioned in the guide, the app must set up a shared container if the app extension uses the NSURLSession class to perform a background upload or download, so that both the extension and its containing app can access the transferred data.

Verifying if the App Restricts the Use of App Extensions

It is possible to reject a specific type of app extension by using the following method:

However, it is currently only possible for “custom keyboard” app extensions (and should be verified when testing apps handling sensitive data via the keyboard like e.g. banking apps).

Dynamic Analysis

For the dynamic analysis we can do the following to gain knowledge without having the source code:

- Inspecting the items being shared

- Identifying the app extensions involved

Inspecting the Items Being Shared

For this we should hook NSExtensionContext - inputItems in the data originating app.

Following the previous example of Telegram we will now use the “Share” button on a text file (that was received from a chat) to create a note in the Notes app with it:

If we run a trace, we’d see the following output:

(0x1c06bb420) NSExtensionContext - inputItems

0x18284355c Foundation!-[NSExtension _itemProviderForPayload:extensionContext:]

0x1828447a4 Foundation!-[NSExtension _loadItemForPayload:contextIdentifier:completionHandler:]

0x182973224 Foundation!__NSXPCCONNECTION_IS_CALLING_OUT_TO_EXPORTED_OBJECT_S3__

0x182971968 Foundation!-[NSXPCConnection _decodeAndInvokeMessageWithEvent:flags:]

0x182748830 Foundation!message_handler

0x181ac27d0 libxpc.dylib!_xpc_connection_call_event_handler

0x181ac0168 libxpc.dylib!_xpc_connection_mach_event

...

RET: (

"<NSExtensionItem: 0x1c420a540> - userInfo:

{

NSExtensionItemAttachmentsKey = (

"<NSItemProvider: 0x1c46b30e0> {types = (\n \"public.plain-text\",\n \"public.file-url\"\n)}"

);

}"

)

Here we can observe that:

- This occurred under-the-hood via XPC, concretely it is implemented via a

NSXPCConnectionthat uses thelibxpc.dylibFramework. - The UTIs included in the

NSItemProviderarepublic.plain-textandpublic.file-url, the latter being included inNSExtensionActivationRulefrom theInfo.plistof the “Share Extension” of Telegram.

Identifying the App Extensions Involved

You can also find out which app extension is taking care of your the requests and responses by hooking NSExtension - _plugIn:

We run the same example again:

(0x1c0370200) NSExtension - _plugIn

RET: <PKPlugin: 0x1163637f0 ph.telegra.Telegraph.Share(5.3) 5B6DE177-F09B-47DA-90CD-34D73121C785

1(2) /private/var/containers/Bundle/Application/15E6A58F-1CA7-44A4-A9E0-6CA85B65FA35

/Telegram X.app/PlugIns/Share.appex>

(0x1c0372300) -[NSExtension _plugIn]

RET: <PKPlugin: 0x10bff7910 com.apple.mobilenotes.SharingExtension(1.5) 73E4F137-5184-4459-A70A-83

F90A1414DC 1(2) /private/var/containers/Bundle/Application/5E267B56-F104-41D0-835B-F1DAB9AE076D

/MobileNotes.app/PlugIns/com.apple.mobilenotes.SharingExtension.appex>

As you can see there are two app extensions involved:

Share.appexis sending the text file (public.plain-textandpublic.file-url).com.apple.mobilenotes.SharingExtension.appexwhich is receiving and will process the text file.

If you want to learn more about what’s happening under-the-hood in terms of XPC, we recommend to take a look at the internal calls from “libxpc.dylib”. For example you can use frida-trace and then dig deeper into the methods that you find more interesting by extending the automatically generated stubs.

UIPasteboard

Overview

The UIPasteboard enables sharing data within an app, and from an app to other apps. There are two kinds of pasteboards:

- systemwide general pasteboard: for sharing data with any app. Persistent by default across device restarts and app uninstalls (since iOS 10).

- custom / named pasteboards: for sharing data with another app (having the same team ID as the app to share from) or with the app itself (they are only available in the process that creates them). Non-persistent by default (since iOS 10), that is, they exist only until the owning (creating) app quits.

Some security considerations:

- Users cannot grant or deny permission for apps to read the pasteboard.

- Since iOS 9, apps cannot access the pasteboard while in background, this mitigates background pasteboard monitoring. However, if the malicious app is brought to foreground again and the data remains in the pasteboard, it will be able to retrieve it programmatically without the knowledge nor the consent of the user.

- Apple warns about persistent named pasteboards and discourages their use. Instead, shared containers should be used.

- Starting in iOS 10 there is a new Handoff feature called Universal Clipboard that is enabled by default. It allows the general pasteboard contents to automatically transfer between devices. This feature can be disabled if the developer chooses to do so and it is also possible to set an expiration time and date for copied data.

Static Analysis

The systemwide general pasteboard can be obtained by using generalPasteboard, search the source code or the compiled binary for this method. Using the systemwide general pasteboard should be avoided when dealing with sensitive data.

Custom pasteboards can be created with pasteboardWithName:create: or pasteboardWithUniqueName. Verify if custom pasteboards are set to be persistent as this is deprecated since iOS 10. A shared container should be used instead.

In addition, the following can be inspected:

- Check if pasteboards are being removed with